Insightview.eu regularly invites experts to write about “special” issues of importance to the financial market. In this context, Joergen Delman, professor, PhD, China Studies, Department of Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies, University of Copenhagen, has been invited to make his thoughts about the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which could be seen as an opportunity as well as a threat to Europe and the United States.

Joergen Delman works on China’s political economy, politics, civil society, climate policies and environmental issues. He is a frequent public speaker and media commentator on these topics and has lived in China for ten years, working as a consultant for international development organisations, as well as Danish and international businesses. He has worked extensively with and within Chinese government organisations at central and local level. Joergen Delman is Co-coordinator of ThinkChina.dk.

Europe, watch out!

In February this year, then German Foreign Minister and Vice Chancellor,

Sigmar Gabriel, warned that the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), also called the “Silk Road” initiative, should not be seen as a sentimental reminder of Marco Polo. In contrast to the liberal world order, argued Gabriel, the BRI “stands for the attempt to establish a comprehensive system for shaping the world in Chinese interest” and to establish a new world system that is not based on freedom, democracy, and individual human rights. Gabriel suggested that the European Union should develop its own similar initiative, especially in relation to Africa. Like the Chinese, he argued, the EU countries should see Africa as an opportunity.

The other EU countries seem to follow suit. In April,

Handelsblatt Global reported that 27 out of 28 EU ambassadors in Beijing (Hungary opted out) had signed a confidential report arguing that the “Silk Road” initiative runs counter to the EU agenda for liberalizing trade and pushes the balance of power in favor of subsidized Chinese companies. A German official commented that China “must take account of the interests of all participants” in the Silk Road initiative.

In February 2018,

Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull attempted to mobilize support from the U.S., Japan, and India to establish an alternative to the BRI. He was supposed to discuss the idea with President Trump during an upcoming visit to Washington. An

US official cautioned, however, that this initiative should be seen as a complement to the BRI, not as a rival. Since then, no further news has transpired about this idea.

China as a modelXi launched the Silk Road initiative in 2013, and a strategy and action plan was

presented by the National Development and Reform Commission in March 2015. From a development policy perspective, the initiative focuses on demonstrating the wider applicability of the Chinese development experience under market socialism since 1978. Silk Road projects were to be implemented along economic development corridors identified by China. The approach reflects what has worked in China: Networks of slow and fast speed trains, roads and highways; airports and harbors; energy infrastructure such as oil and gas pipelines and associated installations, hydropower and renewable energy infrastructure; high-tech communication networks, such as fibernet and mobile networks; business development through special industrial parks, and entrepreneurship programs. China also tests new approaches to cultural diplomacy and investments. The BRI receives substantial financing from the Chinese government and state-owned financial institutions, but local and international co-financing is considered essential for many large-scale, loan financed projects.

Whereas the Silk Road initiative originally focused on connectivities across the Eurasian continent, it now covers most of the world – on land, by sea, and in the air, and it seems that only the sky is the limit for China’s global web of Silk Roads these years. A

Maritime Silk Road initiative has been added, and

Africa became involved early on. In January 2018,

Foreign Minister Wang Yi attended a meeting between China and 33 members of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) where he invited them to join the BRI, since they were a “natural fit”. In January 2018, China announced an

Arctic policy and expressed the wish to develop a ”Polar Silk Road” with

three Arctic sea lanes.

Complex goalsThe BRI reflects Xi Jinping’s new geopolitical doctrine. China is shifting from being a responsive to becoming an active major power. Xi argues that China has entered a

new development stage. At the same time, China is moving ahead from the original “

Going Out” policy from 1999 which primarily focused on acquisition of resources. It is now evident that China is pursuing a new version of its “Going Out” policy that focuses on exporting Chinese equipment, solutions, and higher value goods and services backed by Chinese investments and export financing.

While China’s intentions are being questioned in the West, the Chinese leadership maintains its ‘innocence’. At the National People’s Congress session in March 2018,

Foreign Minister Wang Yi reiterated what Xi has said before: ”The building of [BRI] is based on being open and transparent and on seeking mutual benefit and win-win [solutions]”.

Within the overall framework, the motives behind the global web of Silk Roads are complex. Originally, China’s leadership wanted to bring development and economic integration to China’s Western regions and to neighbouring countries through economic corridors. But on top of this, agreements like the

China-Pakistan Economic Corridor also opened new strategic opportunities for China by offering access, in this case, to the Indian Ocean and the Arabian Sea. China can also use the BRI to export its

well-documented excess capacity in the heavy industries, thus reducing the risk of closures of loss-making state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

On the institutional side, China has often criticized the existing international financial institutions (IFI) for lack of focus on infrastructure development.

Their investments in infrastructure have been declining and only ADB has responded to the Chinese criticism in recent years. Furthermore, China is dissatisfied with IMF and the World Bank for their skewed voting rights that favor the OECD founding partners. China also finds that the IFI procedures are bureaucratic, slow, inefficient, and costly, and that project approvals are too slow.

Finally, China’s ambition to be at the forefront of new cutting-edge industries within health, AI, energy, green energy vehicles, mass transit transport, the internet of things, etc. also prompts China to promote Chinese designs, solutions, and standards globally.

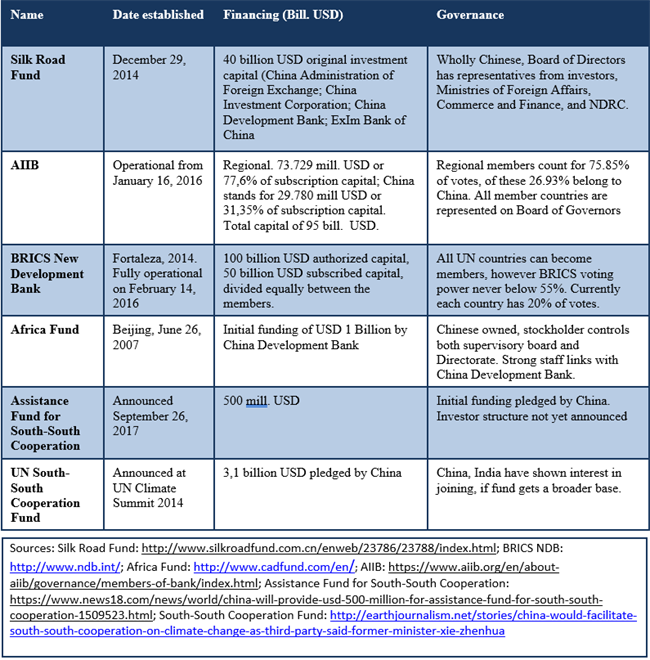

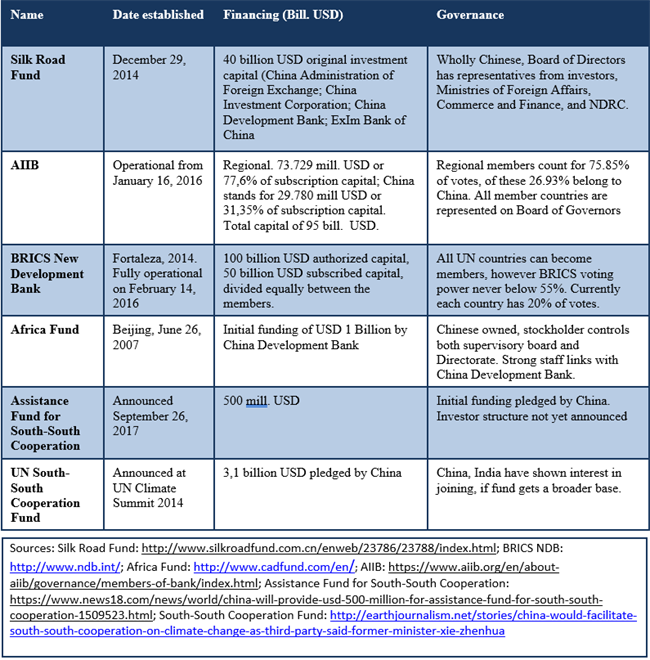

A Chinese push to gain global cloutChina’s new global ambitions have led to the establishment or incorporation of a comprehensive set of financial and political institutions connected to the BRI umbrella. The major financial institutions are shown in the Box.

The

Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB) is meant to be lean, green and clean. The governance structure and the banking procedures are modeled on the principles of the other IFIs, but with China and Asian member countries holding the majority vote. Other countries are invited to participate, and projects are open to international co-financing and bidding. So far, the

Silk Road Fund is China’s own business although it does invite co-financing from outside. These institutions are backed massively by China’s own commercial and policy banks, including

China ExIm Bank.

On the political side, China has established a

Belt and Road Forum and is about to launch a Global Blue Economy Partnership Forum for the Maritime Silk Road. The political connectivities of the BRI will be further consolidated through existing platforms, dialogues, fora, and organizations that China has been instrumental in creating in recent years, such as Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), the

Boao Forum for Asia, Cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries,

China-Arab States Cooperation Forum (CASCF), the

China-Gulf Cooperation Council Strategic Dialogue, and the

China-Pacific Island Countries Economic Development and Cooperation Forum.

China will also put BRI on the agenda of existing regional organizations where it has a strong voice such as

Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO),

The East Asia Leaders' Meetings,

Asia Cooperation Dialogue (ACD),

Greater Mekong Sub-region (GMS), and

the Partnership in Environment Management of Seas of East Asia (PEMSEA).

Further, China will promote and collaborate on the BRI in relation to well-established platforms such as ASEAN Plus China (10+1), Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM), Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia (CICA), Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC). Finally, China will engage organizations where it is a dialogue partner such as:

The Arctic Council and

The Indian Ocean Rim Association.

Existing international organizations are also targeted for BRI- related collaboration.

On the business side, China is active in a host of business associations, industrial parks, and entrepreneurship programs in relation to the BRI. China will establish

two international commercial arbitration courts on Chinese soil that will deal specifically with commercial disputes in relation to BRI initiatives.

China changes the physical and political world mapChina’s engagement in critical infrastructure under the BRI umbrella across the world is changing the global physical, economic, political, and security landscape. The Silk Road projects are multi-scalar, multi-dimensional, and multi-sited. They include massive infrastructure on land, along sea routes and even on sea. Much of this is under the control or management of Chinese SOEs. In 2017,

official Chinese sources disclosed that about 50 Chinese state-owned corporate giants have invested or participated in nearly 1,700 projects in countries along the new Silk Road routes since 2014. In April 2017, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce announced that China was involved in building 56 industrial parks or economic zones, with more than 1,000 companies already doing business there.

Effectively the BRI is setting the framework and conditions for much of tomorrow’s logistics infrastructure. China is promoting new standards for connecting the world, for making it smaller, and for promoting local development where nobody wanted to put their money before. Chinese companies, primarily SOEs, are using this to explore new roles as global ‘Dragon Heads’, a Chinese metaphor for national champions that are instrumental in building strong, transformative, and often quasi-monopolistic conglomerates spanning entire value chains.

The Silk Road initiative has no confines. In April 2017,

Foreign Minister Wang Yi said that China “has no intention of designating clear geographic boundaries for the Belt and Road…it is an initiative for international cooperation in its essence, and should be open to all like-minded countries and regions.” Wang added. “The initiative is not a member’s club, but a circle of friends with extensive participation.”

Where will this take the world? “President Xi believes this is a long-term plan that will involve the current and future generations to propel Chinese and global economic growth,”

said Cao Wenlian, a leading official working on the BRI initiative. He added: “The plan is to lead the new globalization 2.0.” The BRI thus presents new opportunities for governments and business around the world, but evidently they must learn to play by Chinese norms and standards.

In sum, the BRI may well have significant development effects across the world. But China is also using it to build a new global governance architecture that will exist in parallel, complement and interact with the existing structures and systems. This architecture embraces new types of political and economic connectivities and organizations that will have China in a dominant role and help China project its influence as a new major power. Since the US is not participating and seems hesitant to respond, Sigmar Gabriel’s call for the EU to watch out is important. Europe has to find new ways to engage with China’s globalization v 2.0 model. Otherwise, it will not be a win-win solution for Europe.

Inger Helen Sørreime has been research assistant on this paper.

14. May 2018 - Iran nuclear deal - Trump 'solves' one problem by making an even larger problem - Updated version

11. May 2018 - China - Monetary statistics continue to slow, as Beijing is still targetting 'excessive' credit expansion

9. May 2018 - Iran nuclear deal - Trump 'solves' one problem by making an even larger problem - The White House continues to boost Chinese global influence

23. March 2018 - By Invitation - Xi Jinping - Emperor in real new clothes

20. March 2018 - China - A short note on the National People's Congress

Within the overall framework, the motives behind the global web of Silk Roads are complex. Originally, China’s leadership wanted to bring development and economic integration to China’s Western regions and to neighbouring countries through economic corridors. But on top of this, agreements like the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor also opened new strategic opportunities for China by offering access, in this case, to the Indian Ocean and the Arabian Sea. China can also use the BRI to export its well-documented excess capacity in the heavy industries, thus reducing the risk of closures of loss-making state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

Within the overall framework, the motives behind the global web of Silk Roads are complex. Originally, China’s leadership wanted to bring development and economic integration to China’s Western regions and to neighbouring countries through economic corridors. But on top of this, agreements like the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor also opened new strategic opportunities for China by offering access, in this case, to the Indian Ocean and the Arabian Sea. China can also use the BRI to export its well-documented excess capacity in the heavy industries, thus reducing the risk of closures of loss-making state-owned enterprises (SOEs).  On the institutional side, China has often criticized the existing international financial institutions (IFI) for lack of focus on infrastructure development. Their investments in infrastructure have been declining and only ADB has responded to the Chinese criticism in recent years. Furthermore, China is dissatisfied with IMF and the World Bank for their skewed voting rights that favor the OECD founding partners. China also finds that the IFI procedures are bureaucratic, slow, inefficient, and costly, and that project approvals are too slow.

On the institutional side, China has often criticized the existing international financial institutions (IFI) for lack of focus on infrastructure development. Their investments in infrastructure have been declining and only ADB has responded to the Chinese criticism in recent years. Furthermore, China is dissatisfied with IMF and the World Bank for their skewed voting rights that favor the OECD founding partners. China also finds that the IFI procedures are bureaucratic, slow, inefficient, and costly, and that project approvals are too slow. The Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB) is meant to be lean, green and clean. The governance structure and the banking procedures are modeled on the principles of the other IFIs, but with China and Asian member countries holding the majority vote. Other countries are invited to participate, and projects are open to international co-financing and bidding. So far, the Silk Road Fund is China’s own business although it does invite co-financing from outside. These institutions are backed massively by China’s own commercial and policy banks, including China ExIm Bank.

The Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB) is meant to be lean, green and clean. The governance structure and the banking procedures are modeled on the principles of the other IFIs, but with China and Asian member countries holding the majority vote. Other countries are invited to participate, and projects are open to international co-financing and bidding. So far, the Silk Road Fund is China’s own business although it does invite co-financing from outside. These institutions are backed massively by China’s own commercial and policy banks, including China ExIm Bank.  Effectively the BRI is setting the framework and conditions for much of tomorrow’s logistics infrastructure. China is promoting new standards for connecting the world, for making it smaller, and for promoting local development where nobody wanted to put their money before. Chinese companies, primarily SOEs, are using this to explore new roles as global ‘Dragon Heads’, a Chinese metaphor for national champions that are instrumental in building strong, transformative, and often quasi-monopolistic conglomerates spanning entire value chains.

Effectively the BRI is setting the framework and conditions for much of tomorrow’s logistics infrastructure. China is promoting new standards for connecting the world, for making it smaller, and for promoting local development where nobody wanted to put their money before. Chinese companies, primarily SOEs, are using this to explore new roles as global ‘Dragon Heads’, a Chinese metaphor for national champions that are instrumental in building strong, transformative, and often quasi-monopolistic conglomerates spanning entire value chains.