By Invitation: China's dilemma - new global climate leader with brown footprints across the world

Insightview.eu regularly invites experts to write about “special” issues of importance to the financial market. Donald Trump's plan to withdraw the United States from the Paris Climate Accord has lifted China's environmental status. Is this really deserved? In this context, Joergen Delman, professor, PhD, China Studies, Department of Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies, University of Copenhagen, has been invited to write an article on the subject.

Joergen Delman works on China’s political economy, politics, civil society, climate policies and environmental issues. He is a frequent public speaker and media commentator on these topics and has lived in China for ten years, working as a consultant for international development organisations, as well as Danish and international businesses. e has worked extensively with and within Chinese government organisations at central and local level. Joergen Delman is Co-coordinator of ThinkChina.dk. __________________________________________

Only twenty months after

President Barack Obama and President Xi Jinping decided to join hands in the fight against climate change in 2015, US President Donald Trump

announced that the US would withdraw from the

Paris Agreement. The expectations amongst

observers have since been that China could assume a new role as a global climate leader, a role that would be fueled by the country’s own green ambitions and its continued commitment to the Paris Agreement.

However, a recent

New York Times article reported that Chinese energy companies will construct nearly half of the new coal power that will go online during the coming ten years. The report was based on data from

Urgewald, an environmental group based in Berlin. Urgewalds’s

press briefing noted that there are plans to expand the world’s coal-fired power capacity by “a staggering 42.8%”. Currently, ver 1,600 new coal plants and units are planned or under development in 62 countries. If built, they would add over 840,000 MW to the global coal plant fleet.

While major coal power companies from around the world take part in this, China plays a key role in the expansion. According to Urgewald, the Chinese companies account for 45% of the projects in their

database, with around one seventh of their projects located outside of China.

China’s coal plans

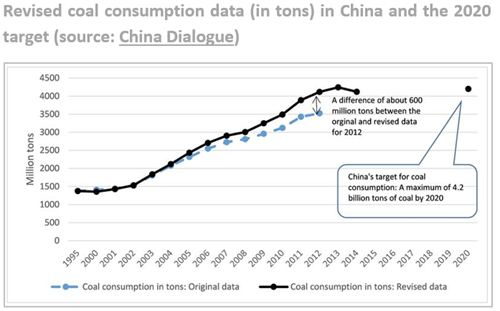

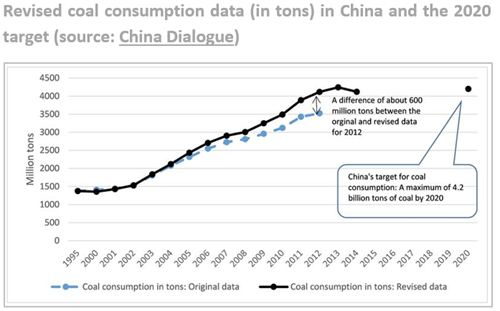

These figures seem to speak against developments in China’s own coal sector, which has seen a drop in consumption from a first peak in 2013. Coal consumption

fell by 2.9% in 2014 and by 3.7% in 2015 in physical tons. With regard to coal’s share of total energy consumption, it actually

fell from 64.0% in 2015 to 62.0% in 2016. The national consumption statistics have been revised upwards since then, due to inconsistencies in data, but the declining tendency in coal consumption seems consistent.

While part of the explanation for the peak in coal can be found in China’s declining GDP growth rates and rigid energy efficiency programs over the last 15 years that have succeeded in decoupling coal-based energy consumption from economic growth, the Chinese leadership has also made up its mind to control the consumption of dirty and bring it down through a broad portfolio of policies. The smog that has pestered China’s major cities in recent years is one of the key drivers behind this.

China’s central authorities have formulated a number of national climate change targets with strong implications for the sectors that produce or use coal. Overall, coal consumption should not account for more than

58 percent of national energy consumption in 2020. Furthermore, an indicative cap of 4.2 billion tons has been set on annual coal consumption (see Chart 1), also for 2020. Finally, China

has set additional targets to peak absolute carbon emissions, to reduce the carbon intensity of the economy by 60-65%, and increase its non-fossil share of the energy supply to 20% in 2030 or even before.

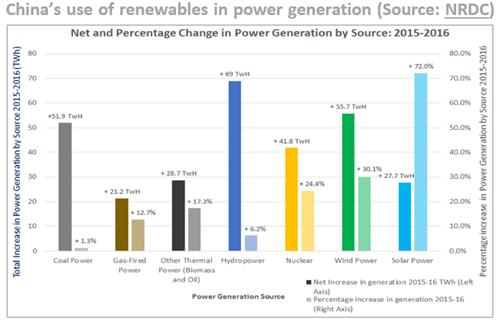

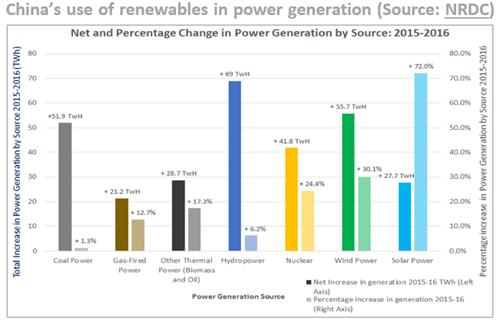

To meet these targets, China will have to cut its use of coal and an increase the use of renewable energy in the power sector during the coming years. In fact, China has already been doing quite well in this respect in its power generation sector in recent years (see the chart above).

While China is making progress with regard to its renewable energy capacity, the bottom line is, however, that coal will continue to be a mainstay of China’s energy production for decades to come. According to the medium-term forecast for coal of the

IEA (2016-2021), China will still account for almost 50% of global coal demand, over 45% of coal production, and more than 10% of seaborne trade. Naturally, the interests associated with this prospect are deeply embedded in the coal sector itself in China, in the power generation sector, in the national grids, in the energy intensive sectors such as steel and cement, and within the highest echelons of the Chinese political elites.

Financing coal vs renewables Therefore, as emerging growth industries, China’s green energy sectors could only develop on the margins of and in competition, if not in conflict with the economically and politically influential coal-driven sectors. Yet, within a short time span, according to

UNEP, China has become the world’s largest investor in renewable energy, with a total investment of USD 102.9 billion in 2015 (excluding big hydro), an increase by 17 per cent y-o-y, representing well over a third of the global total investment in renewable energy. The US was a remote second, with $44.1 billion, up 19%.

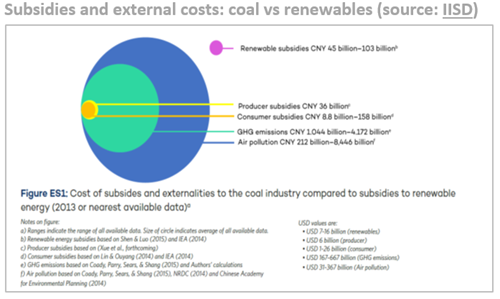

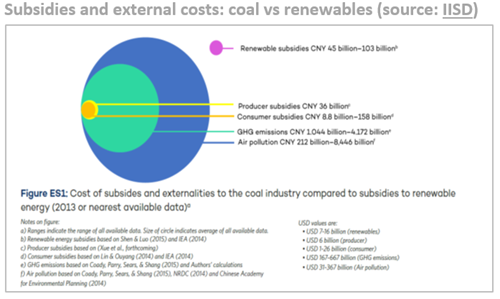

Despite opposition from coal interests, the Chinese top leadership has thus managed to push pro-renewables policies forward, including a broad array of producer and distributor subsidies. However, a

recent report from International Institute of Sustainable Development (IISD), found that China continues to subsidize coal to an extent where the combined cost of subsidies and externalities to society (the cost of dirty coal to human health, e.g. through air pollution, and environmental costs) dwarfs the cost of subsidies to renewable energy. Subsidies have brought the price of coal down and at the same time coal-fired power plants are subject to guaranteed procurement contracts. This ensures that they may continue to run, even when their energy is not needed, while renewable generators face trouble with price competitiveness and with access to the grids. The chart below shows coal subsidies and external costs on the left side, and subsidies to renewables on the right side (purple) in proportion to each other.

Although in transition, the policy regimes clearly continue to favor coal.

ISSD found that the consequence of this situation is that the government is currently overseeing an increase in coal generation capacity from 978 GW, with 227 GW under construction and 563 GW at various stages of planning. This compares with 99 GW of intermittent renewables and 88 GW of non-coal thermal generation under construction (187 GW total non-coal), and 421 GW of intermittent renewables and 164 GW of non-coal thermal generation currently planned (585 GW total non-coal). Renewables and other clean energy sources will thus remain a small fraction of the total energy system for a long time to come.

Continuing global emissions from coalDespite of this,

UNEP points out that renewables attracted more than double the $130 billion committed to new coal- and gas-fired power stations in China in 2015. This was the largest differential ever in favor of renewables up till the end of 2015. In the future, renewables are thus likely to be pushing coal aggressively in China. But

UNEP also notes that leading forecasting organizations estimate that emissions from the global power sector will grow more than 10% between now and 2040, with no prospect of a peak being reached until the late 2020s at the earliest. The CO2 content of the atmosphere looks set to rise sharply beyond the 2015 average of 401 parts per million.

Although this tallies with China’s own plans, China will now move into the spotlight for not accelerating the reduction of the use of coal to a greater extent than we have seen until now. This is where China’s foreign coal projects may hit China’s potential climate leadership as a boomerang.

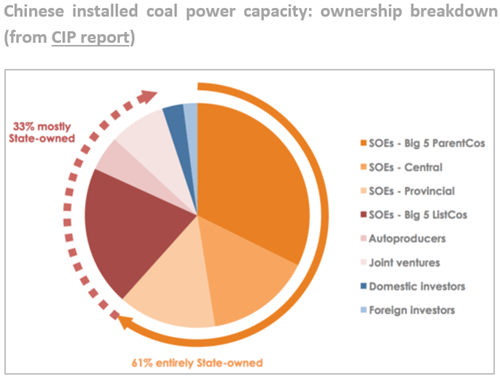

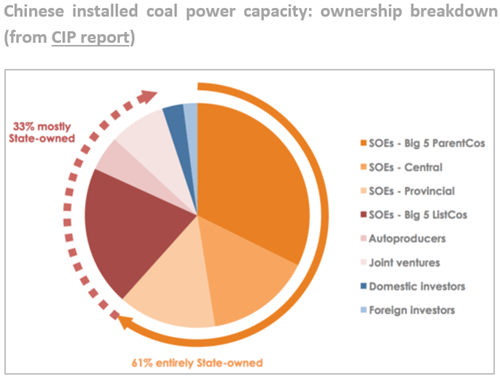

Transformation of the coal power sectorIf the situation in the coal sectors does not change with the current policy regime, the government could well try to use traditional top-down command-and-control methods to make the coal related sectors toe the line, since the majority of the stakeholders dealing with coal are linked to or owned by the state, one way or the other. A 2015 report from the

Climate Policy Initiative (CIP) showed that the majority of all installed coal power capacity is owned by state shareholders in China. 61% were fully controlled by SOEs and they had own controlling shares in 33% of the remaining installed capacity (see the chart below) - click

here to see a map with more details.

However, according to

CIP, SOEs have become increasingly independent financially, and they can now develop and operate coal power without relying on substantial external finance, positive profits, or continued policy support. Due to their financial capacity, the biggest SOEs have a virtual monopoly on deploying the newest and cleanest coal technology, so-called ultra-supercritical coal-fired plants with high upfront costs that is increasingly becoming the industry standard, and which is a much cleaner type of technology than traditional coal power technology.

In fact, a recent

report from the Center for American Progress (CAP) found that the Chinese coal sector is undergoing a fundamental transition these years towards becoming cleaner and greener. China’s new coal-fired power plants are cleaner than anything operating in the United States and China’s emissions standards for conventional air pollutants from coal-fired power plants are stricter than the comparable U.S. standards.

While the demand for new coal power is dwindling at home, the Chinese SOEs appear to be exploiting opportunities to export their financial, physical, and technological capacity to other countries, seeking dividends on their investments. In this context,

CIP notes that overall there is very limited potential for domestic and foreign private investors to impact the electricity generation mix or SOEs’ capital expenditure and expansion plans since the assets are still controlled exclusively by the SOEs themselves.

Climate leader?When President Trump decided to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, he was widely accused of sacrificing the common efforts to keep down global warming for the sake of creating a few tens of thousands new jobs in the domestic coal sector. In response to Trump’s decision,

Michael Bloomberg observed: “The fact is, putting coal miners back to work is no more possible from a business standpoint than putting telegraph operators back to work taking Morse code or putting Eastman Kodak employees back to work manufacturing film rolls.”

Trump presented his decision in a wider perspective, however. He called for a new policy of "energy dominance” as part of his effort to make the US great again. Trump’s Energy Secretary,

Rick Perry, explained to the White House press corps what this means: "An energy dominant America means self-reliant. It means a secure nation, free from the geopolitical turmoil of other nations who seek to use energy as an economic weapon”, and: "an energy dominant America will export to markets around the world, increasing our global leadership and our influence." The ambition is clear: Trump wants the US to be a dominant player in the global energy markets again, recognizing that old, dirty and brown energy is not going to go away for decades to come.

While many deplore that the current regime for coal power financing in the US and China and abroad will lock in CO2 emissions for decades to come, China is bound to focus, not on its energy dominance but on its energy independence, even if the climate is at stake. The future battlefront between China and the US will be between the “energy dominance” of the US and the “energy independence” of China, and coal remains a key to China’s energy independence for the next few decades. This means that China will continue to use coal, but it will not affect China’s overall energy policies with their focus on a green transition of the energy system within the next few decades. Coal is definitely becoming cleaner with new technologies coming on stream. With the right policies, the green transition of China’s energy system might even happen ahead of time as argued ‘theoretically’ in a recent high renewable energy penetration scenario for 2030 undertaken by

China National Renewable Energy Centre.

Even so, China is likely to continue exporting coal power plants and technology to other countries. It is clearly a dilemma as stated by

Trusha Reddy, Coordinator of the International Coal Network: “If the Chinese government truly wants to position itself as a global climate leader, it needs to rein in its state-owned companies that are flooding the world with new coal power plants.”

Thus, China may not be the climate leader the green world is hoping for. The Chinese leadership is facing many contradictory political agendas in relation to clean energy, and the key actors in the coal sectors have proven difficult to rein in. It is encouraging, however, that China is now driving new technologies that have already made and will increasingly make coal cleaner than now, and with more renewables coming on stream the demand for coal will continue to wane.

This article was written with research assistance from Inger Helen Søreime.

This article is also available in the monthly newsletter,

Insightperspectives.euTo subscribe, contact

info@insightview.eu

However, a recent New York Times article reported that Chinese energy companies will construct nearly half of the new coal power that will go online during the coming ten years. The report was based on data from Urgewald, an environmental group based in Berlin. Urgewalds’s press briefing noted that there are plans to expand the world’s coal-fired power capacity by “a staggering 42.8%”. Currently, ver 1,600 new coal plants and units are planned or under development in 62 countries. If built, they would add over 840,000 MW to the global coal plant fleet.

However, a recent New York Times article reported that Chinese energy companies will construct nearly half of the new coal power that will go online during the coming ten years. The report was based on data from Urgewald, an environmental group based in Berlin. Urgewalds’s press briefing noted that there are plans to expand the world’s coal-fired power capacity by “a staggering 42.8%”. Currently, ver 1,600 new coal plants and units are planned or under development in 62 countries. If built, they would add over 840,000 MW to the global coal plant fleet.